New publication — Five years of offsetting native vegetation: The challenge of achieving no-net-loss

A common response to the growing impacts of human activities on nature has been the implementing of biodiversity offset policies. They aim to ‘offset’ the biodiversity impacts of development by undertaking actions that generate equivalent biodiversity gains elsewhere. When offsets work, we refer to them as achieving ‘no-net-loss’ (NNL) of biodiversity. Offset policies have been implemented by governments around the world and the New South Wales (NSW) Government in Australia has one of the oldest and most comprehensive offset schemes in the world.

We have just published a paper where we analysed five years of data from across NSW, containing information on where native vegetation is being cleared for development and where management and restoration are occurring through biodiversity offsets. The publication is available here:

Gordon A., Curtsdotter A., Oliver I., Hernandez S., Cox M., Dorrough J. (2025) Five years of offsetting native vegetation: The challenge of achieving no-net-loss. Ecological Indicators.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2025.114180.

The data we had access to didn’t allow us to undertake an assessment as to whether the development-offset trades are delivering NNL of biodiversity. However, we were able to undertake a detailed analysis of types and condition of vegetation being impacted and offset, as well as exploring risks and uncertainties associated with delivering biodiversity gains under the NSW offset scheme.

At the program level, we conclude that the current scheme is unlikely to achieve NNL. However, the great news is that the NSW Government has now committed to updating its offset scheme to deliver nature positive outcomes (e.g., see here and here.). The recommendations in our paper should be useful for updating the NSW scheme over the coming year.

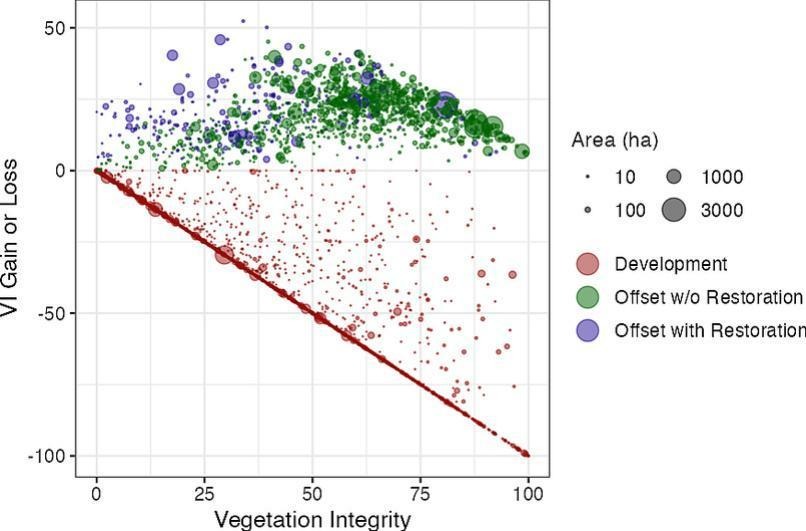

The above image is the most interesting data visualization in our paper (we referred to it as the ‘watercolour plot’ when writing the paper). It’s a scatter plot showing the loss or gain in vegetation condition from developments and biodiversity offsets (y-axis) as a function of the initial vegetation condition of the development or offset (x-axis). The red dots on the diagonal line show cases where a development resulted in complete clearing of vegetation. Red dots above this line show cases where a development did not result in complete loss of native vegetation. The purple and green dots show the predicted biodiversity gains (over 20 years) resulting from offset activities. This plot emphasises the problematic nature of biodiversity offsets: the trading of permanent immediate losses of biodiversity for a gradual (and uncertain) accrual of biodiversity gains over longer time periods.

Thanks to co-authors: Josh Dorrough, Alva Curtsdotter, Michelle Cox, Ian Oliver and Steph Hernandez and the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water for funding this research.

I’d like to end by acknowledging the research was undertaken on the lands of the Wurundjeri People comprising the Woi-wurrung and Boon Wurrung language groups of the Kulin Nation, and on the lands of the Djiringanj and Thaua People of the Yuin Nation. The paper refers to data from across NSW, Australia and we acknowledge the Aboriginal peoples as the custodians of the land, waters, and sky of NSW.